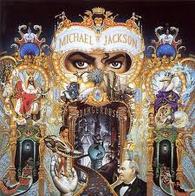

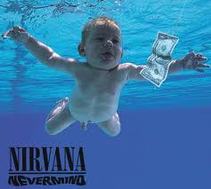

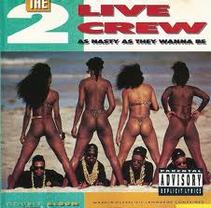

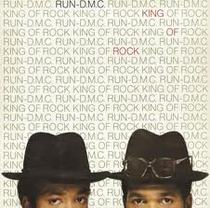

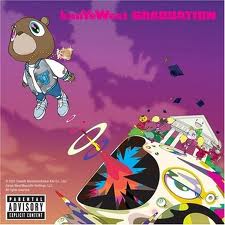

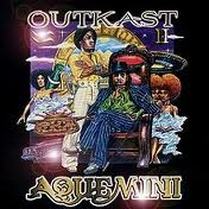

Written by Amilcar 'PRO' Welton / Executive Director / CREATE.Digital Music Whatever happened to album cover "artwork"? This would include single covers, E.P. covers and even recent quality mixtape covers. Since day one of retail music consumption, covers have been one of the major attractions during the consumer music purchasing experience. Photographers, artists, and graphic designers were commissioned to make music lovers buy and cherish their physical units. The perfect artwork along with popular music made for a complete music experience, especially before the invention of television. When entering a record store, potential buyers use to graze shelves and crates of releases for hours searching for music that they knew and music that they were willing to take a chance on. Eye catching covers helped you make that decision...a creative logo...an attractive man or woman...a tricked out car....big guns....partial nudity....all forced buyers into unexpected decisions. When the "music made easy" explosion in the late 1990's and early 2000's started, there was a substantial amount of people creating music for consumption by way of digital music production equipment and independent distribution outlets. In my opinion, this is when cover art was at its highest value. Just ask Percy "Master P" Miller and No Limit Records. Ask Sean "Diddy" Combs and Bad Boy Records. Their cover art helped propel their artists and constant flood of music releases above others. As an independent label during that time, your cover art had to jump off the shelves visually in order to even have a slight chance to sway a consumer's decision. Even as online music outlets were introduced, you needed to visually differentiate yourself from the millions of releases available as consumers "surfed" the internet. I believe that the decline of the business and creative value of cover art began in the 1990's. Music creators, both independent and major, began to shift budgets into multi-million dollar music videos, extravagant tour sets, and exaggerated lifestyles for their artists. That along with the high volume of projects being released, adversely affected the dedication, creativity, and quality of on staff and outsourced graphic designers. Ask yourself, how can you have an artist post new photos from multiple photo shoots every other day yet they still end up with subpar cover art? I agree with the fact that music videos became the visual focus but cover art was not suppose to be written off like audio cassettes when the CD was introduced. I'm also not saying that the graphic designers didn't do their job but most did exactly that..."their job" and nothing more. They stopped believing in the impact of their creativity and influence on the music. They simply focused on being just another gear in the machine. For outsourced graphic designers it may also have been the fact that it took approximately 6 months to get their checks from the record labels, if they got them at all.

Please don't take this organized rant as a blanket statement regarding all cover artwork, all record labels, all graphic designers, etc. I just wanted to express my disappointment in what I see on average and I see tons of music releases both independent and major. Just as people complain about a lack of feeling, effort, and creativity in music, the same goes for cover art. What is the resolution? Well, it starts with the artists. It requires that independent attitude that has propelled music in recent years. The creators of music must hold themselves to a higher standard and include cover art in their musical revolution. Don't settle. Just as you would correct a bad note, an average mix, a dull lyric, challenge yourself to want more from your artwork. Challenge your team, management, graphic designer, and label. If you take a moment to think back to your favorite albums, I guarantee at least one of them had classic artwork.

6 Comments

There's been much speculation as to the enormous amount of money Psy must have raked in from the hundreds of millions of hits his Gangnam Style video has had on YouTube. There's no way of knowing for sure, as all Google/YouTube deals are covered by non-disclosure agreements – and do not allow independent labels to demand audits. However, the chances are that though the amount won't be insignificant, it will be much lower than one might think. And, judging by the royalty statements that just landed on the doormats of songwriters all around the world, we can be certain that the co-writer of the track didn't earn a fortune off YouTube.

As a matter of fact, one of the songwriters' forums on Facebook was alight with angry – and sometimes despondent – postings of royalty statement screengrabs. Ellen Shipley, the co-writer (with a 50% share) of Belinda Carlisle's Heaven Is a Place On Earth reported receiving $38.49 for the 2,118,200 streams the track had accumulated on YouTube in the last quarter. For the over 330,000 hits her 'N Sync track I Drive Myself Crazy had on the video site, she received $4.31. "I can't even buy a pizza for that," she pointed out. Another songwriter reported getting about $80 for 9m YouTube streams. The discrepancy in rates may be attributed to the fact that YouTube does not have a licence agreement with performance rights societies in countries such as Sweden, despite being available there, so streams from those countries don't result in any royalties at all. It may also be attributed to the fact that, at least in the UK, YouTube paid PRS for Music a lump sum back in 2009 for usage until 2012 (they're currently in licence negotiations covering future usage), which means the more hits YouTube videos get, the less songwriters get paid per hit. Now, some may claim that YouTube is just a discovery tool and so, like MTV back in the day, should not be an income stream for artists and songwriters. But, as with MTV, record labels have realised that they're spending millions on the music videos from which YouTube – without having to pay anything for the content it hosts – is earning big advertising revenue. And, unlike MTV, YouTube is "on demand". A recent Nielsen survey discovered that listening habits are changing, as 64% of US teenagers mainly listen to music on YouTube – a revelation that may confirm predictions that, in the future, streaming will be the main way music is consumed. As YouTube playlist generators become more commonly used, that number may still rise, since the user doesn't have to click on a new link every time a track finishes. If that is indeed the case, it appears professional artists and songwriters better get busy looking for another day job. But YouTube wasn't the only target of the songwriters' Facebook posts. "Pandora report. 1.5m plays – and I received $12.84! WTF???? Pandora can go F$$K itself," wrote one of them below his royalty statement. Another called the $6.78 he made from 633,100 spins on Pandora of his Josh Groban track "an insult". Though master rights holders (owners of the recordings) get higher royalties, labels and artists (including online phenomenon OK Go) have also conceded the income from streaming services such as YouTube and Pandora are negligible – with Spotify being the exception (at least in Sweden). One Swedish independent label told of how the monthly 100,000 streams his artists generated on Spotify earned the label £94 – a rate he considered reasonable. He deemed the publishers' (songwriters') share "negligible", however, and he pointed out that, unlike terrestrial radio, the musicians playing on the track did not get anything at all from Spotify. In June this year Kalle Magnusson, who runs the Swedish independent record label Hybris, said Spotify has been a lifeline for the country's labels, which have suffered immensely in the past decade as record sales bottomed out. He claims four out of five Swedish Spotify users pay for the service (a Swedish publishing executive I spoke to claimed a tenth of the population – 900,000 – subscribe to it), and revenue per play had nearly tripled for the label in the past 12 months. He said 80% of Hybris's revenue now comes from Spotify. While Spotify royalties appear to slowly increase, as the number of subscriptions rise, Pandora – an interactive, ad-supported sort of hybrid of Spotify and radio – wants to further reduce its royalty commitments, despite having been content with the statutory webcasting rate when it was agreed in 2009. The company's founder, Tim Westergren, now argues that since satellite radio (such as Sirius XM) pay less than 10% of their revenue in royalty payments, while Pandora pays more than twice that – and terrestrial radio in the US doesn't have to pay performers and record labels at all (though they do pay songwriters), it's an unfair playing field. It's worth noting, however, that the US is one of less than a handful of countries – including North Korea, Congo and China – where artists don't get paid for airplay. So perhaps a more reasonable way of creating a level playing field would be to demand American terrestrial radio corporations fall into line with almost every other country in the world by paying artists when they use their music. Westergren claims that he cares about musicians as, he says, he is one himself. Yet, after Pandora went public with an IPO at a $1.6bn valuation, it appears Westergren is more concerned with pleasing shareholders than supporting musicians. He is currently urging consumers to write to their congressman, demanding they vote for the proposed Internet Radio Fairness Act, which would cut royalty rates for internet radio. So far Pandora has spent more than $500,000 on lobbyists as well as making more than $100,000 in political campaign contributions in 2011/12 alone – and it's a top contributor to Rep Jason Chaffetz, the man who introduced the IRFA in Congress, according to Open Secrets. If Pandora truly cares about musicians but has trouble balancing its books, maybe it should stop spending all that money on lobbying for even lower royalty rates. As David Lowery put it in his Trichordist blog: where is it written that Pandora is guaranteed the right to stay in business when musicians aren't? If Pandora thinks paying a decent rate for the music that is the sole reason for its existence is unsustainable, maybe – to use an argument thrown at the music industry over and over for the past decade – it's because its business model is flawed and it should come up with a new one. As for YouTube, a company that has no significant competitors and is far from in the red, how about paying songwriters a decent royalty rate so they can at least afford a whole pizza for what they earn from hundreds of thousands of hits on YouTube? |

MISSION The purpose of the CREATE.Digital Blog is to provide an interactive knowledgebase & promotional platform focused on quality not quantity. AUTHORS

Contributors to the CREATE.Digital Music Blog will include internal staff & a variety of professional, qualified, opinionated, diverse, & experienced guests. ARCHIVES

May 2024

CATEGORIES

All

DISCLAIMERPLEASE READ

All the contents of the CREATE.Digital Blog, except for comments, constitute personal opinions. Blog content may contain inaccuracies or errors, and discretion should be exercised in the use information obtained from the blog. Blog content is provided for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for advice from qualified professionals. All blog content comes without warranties, representations, or guarantees of any kind. You agree that any use you make of blog content is at your own risk. You also agree that CREATE.Digital Music is not responsible for any losses resulting from your reliance on any blog content. We also reserve the right to revise any and all content on the blog at any time. If you report offensive or inappropriate comments to CREATE.Digital Music, We will generally investigate and remove comments if required. All blog content, including all information, text, graphics, photos, images, logos, and site design, is our intellectual property, and is protected by copyright and applicable intellectual property law. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed